Throughout history the story of humans and the Honeybee have been intertwined. Long sought after for their honey, honeybees have been depicted in ancient cultures and modern religions as a symbol of fertility, industriousness, and cooperation. From prehistoric cave drawings depicting honey gatherers in southern Africa, Asia, Australia, and Europe, to modern agriculture heavily relying on the Honeybee for their crop pollination services; the Honeybee has played a key role in the development of human traditions, agriculture, and society.

Mesolithic (Stone Age) Honey Gatherers

The earliest found record of honey gathering is depicted in the Cave of the Spider (la Cueva de la Araña) near Valencia, Spain. This 15,000 year old painting shows a woman on a rope ladder gathering honey from a bee nest precariously on the side of a rock cliff. Other such drawings show similar depictions of people gathering honey in the wild, where honeybee nests are usually found high-up in cavities of trees and the side of rock cliffs.

This method of gathering honey is still practiced in many parts of the world today. Such examples of this include the Bedouin tribes in the Syrian desert, the Veddhas people of Sri Lanka, and the Gurung group of Nepal. For many of these people gathering wild honey can be a valuable source of income, food and serve an important part in rituals.

Ancient Egyptian Beekeeping

The earliest known form of organized beekeeping occurred in ancient Egypt, where twig and reed designed hives would allow beekeepers to manage honeybee colonies, of a species known today as the Egyptian Honeybee (Apis mellifera lamarcki). By 1500 BCE, beekeeping was widespread throughout the Nile region with Egyptian administrators accepting honey presented by farmers as payment. With this, honey was collected in clay vessels and stamped according to their quality and colour.

Honeybee products were not only a source of food, but also used for medicinal purposes and religious practices. Honey was commonly used as an antiseptic to treat wounds, and was a common offering to the Egyptian Gods. Beeswax also was used for candle making and an important substance used in the mummification process. According to Egyptian mythology, when Ra, the god of the sun cried his tears would turn into bees so that they would bring fertility by pollinating the flowers of the Nile.

Ancient Chinese Beekeeping

While there are no existing records of Mesolithic honey gatherers in China, it is likely that some groups of people did harvest honey from the wild honeybee populations. There are three species of honeybee native to China, including the Dwarf Honeybee (Apis florea), the Giant Honeybee (Apis dorsata), and the Eastern Honeybee (Apis cerana).

Apiculture has a long history in China, where the native Eastern Honeybee, has been used for crop pollination, as well as honey and beeswax production. Although the Eastern Honeybee forages in a smaller area and produces less honey than its European counterpart, by the time of the East Han-Dynasty (25-150 CE) beekeeping was well established and highly profitable. With this, early records reference professional beekeepers and an industry forming around the production of honey and wax for the Emperor, his court, and the educated elites.

Ancient Mayan Beekeeping

Prior to contact with the Spanish in Mesoamerica during the 16th century, the Mayan culture had existed for over 1,800 years. It is believed the Mayan had a greatly developed knowledge of beekeeping, being able to divide existing hives to increase numbers and taking care to not over-harvest in order to leave enough honey stores for the honeybees. According to early Spanish accounts the Mayan had well-established apiaries with hundreds and sometimes thousands of native Stingless Honeybee hives. Each hive was made from hollowed-out logs in the shape of large drums, which were individually carved featuring figures, ornaments, and the sign of the owner of the hives. The bees would enter and leave a hole in the middle of the hive, with round stone discs being used as end stoppers. These stone discs are the oldest known beekeeping artifacts in the world, dating between 300 BCE and 300 CE.

The honeybee species used by the Mayan is native to Mesoamerica, being called the Stingless Honeybee (Melipona beecheii) for its lack of stinger for defense. The Stingless honeybee typically builds its nests inside cavities of trees, being observed in tropical rainforests around the Yucatan region of modern day Mexico and Central America. Sadly, due to severe deforestation, widespread insecticide use, as well as the arrival of European and African Honeybees, it is estimated that Stingless Honeybee populations have decreased over 90% in the past two decades.

Beekeeping through the European Middle Ages and Colonial Periods

Honey gathering practices in medieval Europe was based on early beekeeping practices seeking out large trees with wild resident honeybees. After finding honeybee nests, beekeepers would cut out small sections of the tree to make protective wood panels with flight entrances so that the honeybees could be easily accessible and protect from bad weather and predators. It was also common for the tops of growing trees to be cut off in attempts to reduce their height and thicken their trunks so it was possible to carve out more artificial cavities in the trees. Throughout northern Europe this model of tree beekeeping was common leading to the creation of “bee forests,” usually owned by the aristocracy or the Church.

Beekeeping in bee forests was important to local European economies, however it was a very time consuming way of beekeeping. Other methods for keeping Honeybees included “log hives” and basket-weave hives known as “skeps.” These methods were utilized in many parts of Eastern Europe especially in the regions of Germany, Poland, and Lithuania. Log hives were essentially cut rounds from trees that contained the nests of honeybees. It would be common for the log hives to then be carved and painted, and in some instances made into sophisticated human figures. In contrast, skeps were typically made out of willow wicker, or a combination of straw, reeds and sedges. The benefits of these methods were the ability to have the hives closer to human settlements and transport them to different locations. In Britain, France, and other parts of Western Europe specially made stone structures called “bee boles” were often erected in south or southeast facing walls near orchards and gardens to protect honeybee hives from wind and rain.

Beekeeping in bee forests was important to local European economies, however it was a very time consuming way of beekeeping. Other methods for keeping Honeybees included “log hives” and basket-weave hives known as “skeps.” These methods were utilized in many parts of Eastern Europe especially in the regions of Germany, Poland, and Lithuania. Log hives were essentially cut rounds from trees that contained the nests of honeybees. It would be common for the log hives to then be carved and painted, and in some instances made into sophisticated human figures. In contrast, skeps were typically made out of willow wicker, or a combination of straw, reeds and sedges. The benefits of these methods were the ability to have the hives closer to human settlements and transport them to different locations. In Britain, France, and other parts of Western Europe specially made stone structures called “bee boles” were often erected in south or southeast facing walls near orchards and gardens to protect honeybee hives from wind and rain.

During the Age of Discovery and the subsequent colonization of the Americas, ship cargo manifests show that European Honeybees were among the first animals to ship with the early settlers. Honeybees were viewed as an essential part of colonial life because the bees would produce precious honey, beeswax, as well as pollinate crops. Moreover, during the period of England’s taxation upon American colonists, honey was used instead of highly taxed sugar. With this, honey and beeswax was an important source of income, and for making products like candles, lipstick, shoe polish, and mead. This led to the spread of honeybees across North America, but it was not until 1856 when honeybees arrived on Vancouver Island, being among the first places in Western Canada.

Modern Beekeeping

Although honey-hunting from wild bees still exists in some societies, the majority of honey is now harvested from managed and kept bees. Today the most widely used beehive design is known as the Langstroth hive which is made up of wooden boxes and individual wooden frames that can easily be removed to harvest honey and wax, as well as inspect the health of the hive. The other benefit of the Langstroth hive is that it can be moved with relative ease. It is common for hives to be migratory throughout the growing season to where the best forage and high nectar yielding flowers are.

In Europe, it is common for beekeepers to move their honeybee hives to the countryside in the latter part of the growing season. In the UK heather is in bloom, and in France the lavender fields perfume the air with the sweet smell of lavender flowers. These varieties of honey can fetch a high price, and so it makes it worthwhile to move the hives. Meanwhile in Central Asia, in the countries of Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and southern Kazakhstan migratory beekeepers move their hives on wagon trains with sometimes up to 300 to 400 hives. When nectar-rich flowers start to bloom in April and May migratory bee wagons will move to the best areas of wildflower forage.

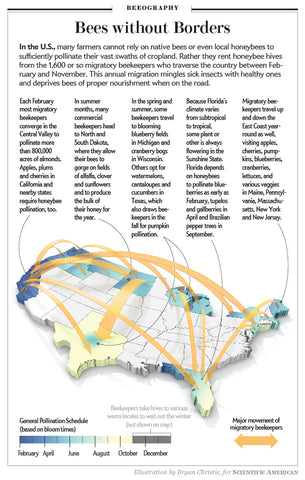

With the establishment of immense fruit, nut, and berry farms In the United States, migratory beekeeping and their pollination services in particular, are the most profitable way to make money Beekeeping. Throughout the main growing season hundreds of thousands of hives are transported on the highways by semi-trucks to large agricultural operations. It begins each February where the largest pollinating event in the world occurs in California with the pollination of over 800,000 acres of Almond groves by honeybees. Subsequently, commercial beekeepers will transport their hives to other parts of the country to pollinate crops like alfalfa in the Mid-West, berries in the North-East, and oranges in Florida. With agriculture relying on such large scale monoculture operations, native pollinating species alone are not enough, and so honeybees are trucked in from around the country for their pollinating services.

Threats to Honeybees and Other Pollinating Species

Today beekeepers have to grapple with the presence of major honeybee diseases, in particular is the bee mite known as Varroa destructor which is one of the likely contributors to the phenomenon known as Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD). In addition, the widespread use and exposure to pesticides, insecticides, and herbicides not only threatens the life of the individual bee, but also the survival of the hive with the contaminated nectar and pollen being shared throughout the hive. The problems of disease and potentially toxic environments are only exacerbated by the lack nectar-rich forage areas year-round, and the movement of bees around for pollination services. Though migratory beekeeping can be successful in terms of greater productivity from the hives, it can be very stressful for the bees making them more susceptible to disease.

Although the migration and spread of the Western honeybee species around the world has brought about improved commercial honey and crop production; unfortunately on a commercial scale it poses a major threat to the well-being and health of not only honeybee populations but also other pollinating species. In many areas of the world, the arrival of the Western Honeybee displaced and introduced diseases to native bee species. In places like Australia there is concern that introduced Western Honeybees are competing for forage with the native stingless bees and other pollinating species. In Canada and the United States there is evidence linking the rise of large scale commercial beekeeping operations, and honeybee diseases being transferable to native bumblebee populations. While in Central and South America, the introduction of “Africanized Bees” has decimated native stingless bees that were historically used by the local indigenous people and the Mayan beekeepers of centuries past.

As Western Honeybees are an introduced species to Vancouver Island and much of the world, it is important to not wholly rely on them for their pollination services, and not forget that other species play an important role in pollinating our food crops and native plant species. With this, honeybees should be looked at as a partner with other pollinators in the pollination services they provide. To overcome these major threats posed to the honeybee, and other pollinating species is to support your local beekeepers and organic agriculture. Through the establishment of healthy and sustainable areas, with a great diversity of forage crops and flowers year round, we can work to overcome the threats posed by disease and commercial monocultures.